Contributions of event rates, pre-hospital deaths, and deaths following hospitalisation to variations in myocardial infarction mortality in 326 districts in England: a spatial analysis of linked hospitalisation and mortality data

Summary

Background

Myocardial infarction mortality varies substantially within high-income countries. There is limited guidance on what interventions—including primary and secondary prevention, or improvement of care pathways and quality—can reduce myocardial infarction mortality. Our aim was to understand the contributions of incidence (event rate), pre-hospital deaths, and hospital case fatality to the variations in myocardial infarction mortality within England.

Methods

We used linked data from national databases on hospitalisations and deaths with acute myocardial infarction (ICD-10 codes I21 and I22) as a primary hospital diagnosis or underlying cause of death, from Jan 1, 2015, to Dec 31, 2018. We used geographical identifiers to estimate myocardial infarction event rate (number of events per 100 000 population), death rate (number of deaths per 100 000 population), total case fatality (proportion of events that resulted in death), pre-hospital fatality (proportion of events that resulted in pre-hospital death), and hospital case fatality (proportion of admissions due to myocardial infarction that resulted in death within 28 days of admission) for men and women aged 45 years and older across 326 districts in England. Data were analysed in a Bayesian spatial model that accounted for similarities and differences in spatial patterns of fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction. Age-standardised rates were calculated by weighting age-specific rates by the corresponding national share of the appropriate denominator for each measure.

Findings

From 2015 to 2018, national age-standardised death rates were 63 per 100 000 population in women and 126 per 100 000 in men, and event rates were 233 per 100 000 in women and 512 per 100 000 in men. After age-standardisation, 15·0% of events in women and 16·9% in men resulted in death before hospitalisation, and hospital case fatality was 10·8% in women and 10·6% in men. Across districts, the 99th-to-1st percentile ratio of age-standardised myocardial infarction death rates was 2·63 (95% credible interval 2·45–2·83) in women and 2·56 (2·37–2·76) in men, with death rates highest in parts of northern England. The main contributor to this variation was myocardial infarction event rate, with a 99th-to-1st percentile ratio of 2·55 (2·39–2·72) in women and 2·17 (2·08–2·27) in men across districts. Pre-hospital fatality was greater than hospital case fatality in every district. Pre-hospital fatality had a 99th-to-1st percentile ratio of 1·60 (1·50–1·70) in women and 1·75 (1·66–1·86) in men across districts, and made a greater contribution to variation in total case fatality than did hospital case fatality (99th-to-1st percentile ratio 1·39 [1·29–1·49] and 1·49 [1·39–1·60]). The contribution of case fatality to variation in deaths across districts was largest in women aged 55–64 and 65–74 years and in men aged 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84 years. Pre-hospital fatality was slightly higher in men than in women in most districts and age groups, whereas hospital case fatality was higher in women in virtually all districts at ages up to and including 65–74 years.

Interpretation

Most of the variation in myocardial infarction mortality in England is due to variation in myocardial infarction event rate, with a smaller role for case fatality. Most variation in case fatality occurs before rather than after hospital admission. Reducing subnational variations in myocardial infarction mortality requires interventions that reduce event rate and pre-hospital deaths.

Funding

Wellcome Trust, British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council (UK Research and Innovation), and National Institute for Health Research (UK).

Introduction

,

This decrease in incidence of myocardial infarction has been due to reductions in risk factors such as smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol in the population, as well as primary and secondary prevention through pharmacological treatment in individuals at high risk.

Improvement in myocardial infarction survival has been achieved by more rapid diagnosis and revascularisation and through the use of anti-platelet agents based on evidence from randomised trials. At the health-system level, the establishment of cardiology wards, coronary care units, and cardiac intensive care units, staffed by specialist cardiac doctors and nurses, has helped to standardise and optimise the delivery of the aforementioned treatments and to identify and intervene on complications early.

Evidence before this study

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) for articles published from Jan 1, 2000, to Dec 6, 2021, using the search terms (“myocardial infarction”[Title] OR “coronary heart disease”[Title] or “ischaemic heart disease”[Title]) AND ((“subnational”) OR (“small area”) OR (“local”)) AND ((“registry”) OR (“incidence”) OR (“mortality”) OR (“case fatality”)). No language restrictions were applied. We started our search from the year 2000 in order to focus on studies after the introduction of primary angioplasty and the use of troponin-based measurements to define myocardial infarction. We also searched for relevant reports through the websites of registries and requests for information from clinicians and researchers in high-income countries in Australasia, Europe, and the Americas. We found some studies from countries in Australasia, Europe, and the Americas that had used data on hospitalised patients and reported myocardial infarction admissions and hospital case fatality for an entire country. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development also reports hospital case fatality for its member states based on countries’ officially reported statistics, but the actual data sources are not stated. Few of these studies included deaths outside of a hospital setting; of these, some had considered all ischaemic heart disease deaths, and only four national studies had specifically focused on pre-hospital acute myocardial infarction deaths. We also found a study that used data from specific communities in six countries to report on myocardial infarction admissions and pre-hospital and hospital case fatality, as had been done in the MONICA study for the 1990s. In terms of subnational studies, we found one study on death rates for ischaemic heart disease for US counties, and two reports of ischaemic heart disease death rates for local authorities in England. These studies did not separate pre-hospital versus hospital fatality or distinguish acute myocardial infarction from chronic atherosclerotic disease and complications; nor did they have data on hospitalisation. We also found one local authority-level study of myocardial infarction hospitalisation rates in England, but this study did not include pre-hospital deaths. To our knowledge, there is no study on subnational variations in myocardial infarction death rate and its complete contributors (event rates, pre-hospital fatality, and hospital case fatality).

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this study provides the only subnational analysis of myocardial infarction death rate and its complete contributors in any country. We used nationwide linked data that capture all forms of myocardial infarction events: non-fatal events and pre-hospital and hospital fatality. We used a spatial statistical model to obtain stable estimates of myocardial infarction event rates and pre-hospital fatality and hospital case fatality by age group for small geographies, together with the uncertainty in these estimates.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our subnational results, together with available national data, show that pre-hospital deaths are a larger contributor to myocardial infarction mortality, and how it varies both within and across high-income countries, than is hospital case fatality. This finding demonstrates the need for research on, and implementation and standardisation of, interventions that reduce time between symptom onset and call for help, as well as the time to initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation in the event of a myocardial infarction leading to cardiac arrest. There is also a need for regular national and subnational reporting of all myocardial infarction deaths, separated by whether the individual had a recent hospital admission, so that the impacts of interventions can be measured.

,

,

Myocardial infarction mortality, and its variation within a population, can be reduced through primary and secondary prevention measures to reduce event rates; improving awareness of myocardial infarction symptoms and initial response time to reduce the share of patients with myocardial infarction who die before reaching a hospital; and improving hospital care. Many current trial and standardisation efforts are targeted towards the latter component.

However, there are limited data on the relative importance of these three contributors to subnational variations in myocardial infarction mortality, which are needed to inform the selection of optimal strategies for reducing myocardial infarction mortality where it is high.

We used linked data on hospitalisations and deaths in England’s 326 local authority districts (political and administrative units that are used for the allocation of public health and social care budgets and for the formulation and delivery of primary prevention; referred to henceforth as districts) to determine how much the geographical variation in myocardial infarction mortality arises from variations in event rates and in case fatality and its constituents, namely pre-hospital death and death following hospitalisation (referred to as hospital case fatality).

Results

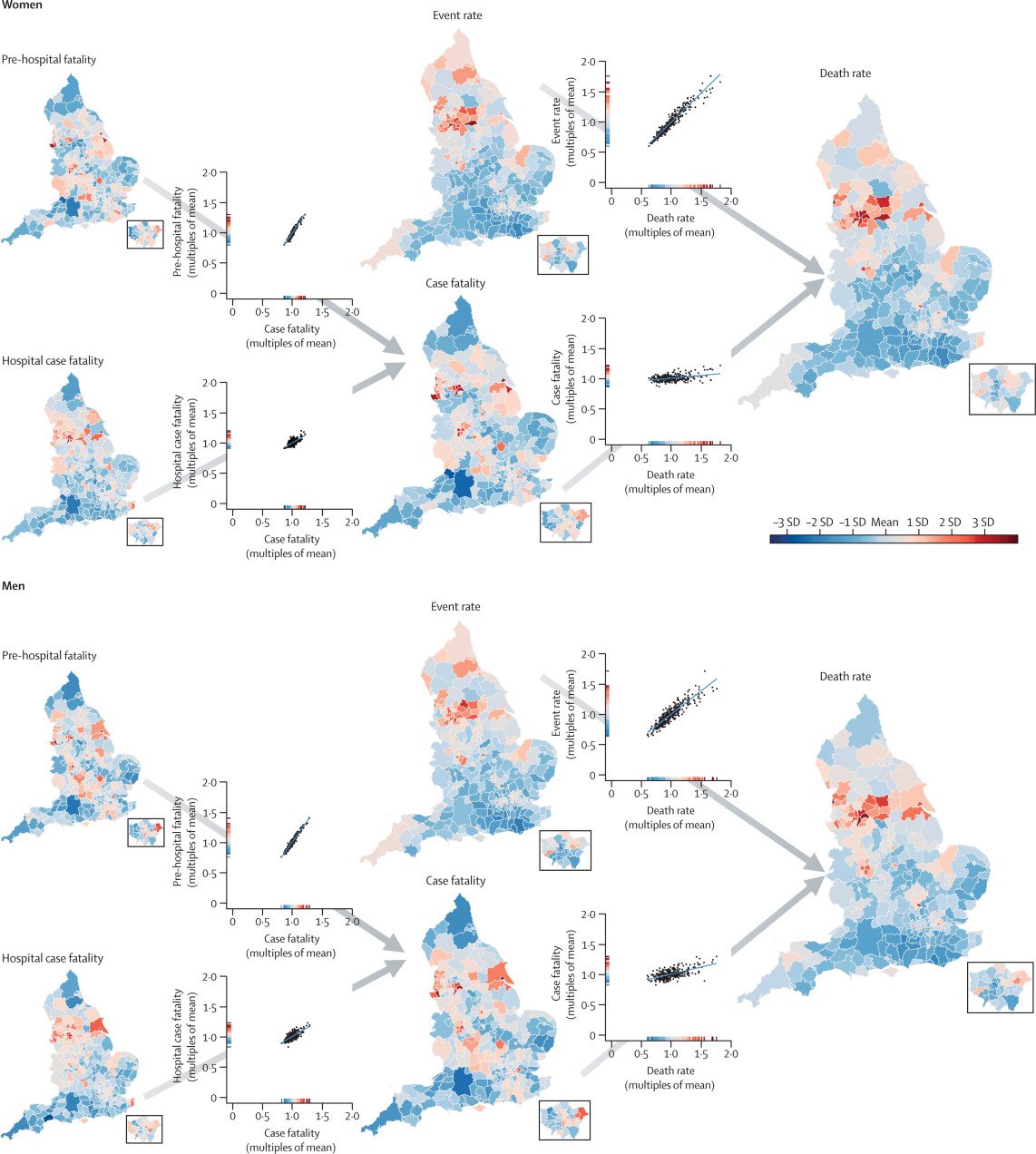

Figure 1Age-standardised acute myocardial infarction death rate and its contributors in districts of England in women and men

The maps show the geography of death rate and each contributor (insets show London). The scatter plots show the relationship between pairs of contributors, or contributors and death rates. All variables were age-standardised. The scale on each scatter plot ranges from 0 to 2 × the mean of the values across all districts to allow the extent of variation to be compared among variables. The colour corresponds to the number of SDs above or below the mean value across all districts. The appendix shows maps and scatter plots with numerical scales (pp 10–11) and the posterior probabilities that the estimated rates and case fatality for each district are higher or lower than the national average (pp 12–13).

Table 1Distributions of myocardial infarction mortality and its components (event rate and case fatality, including pre-hospital fatality and hospital case fatality) across 326 districts in England

Mortality, event rate, and fatality all apply to myocardial infarction. Numbers in parentheses are 95% credible intervals. The best performing and worst performing districts (ie, the individual districts with the lowest and highest values, respectively) could be different for each outcome.

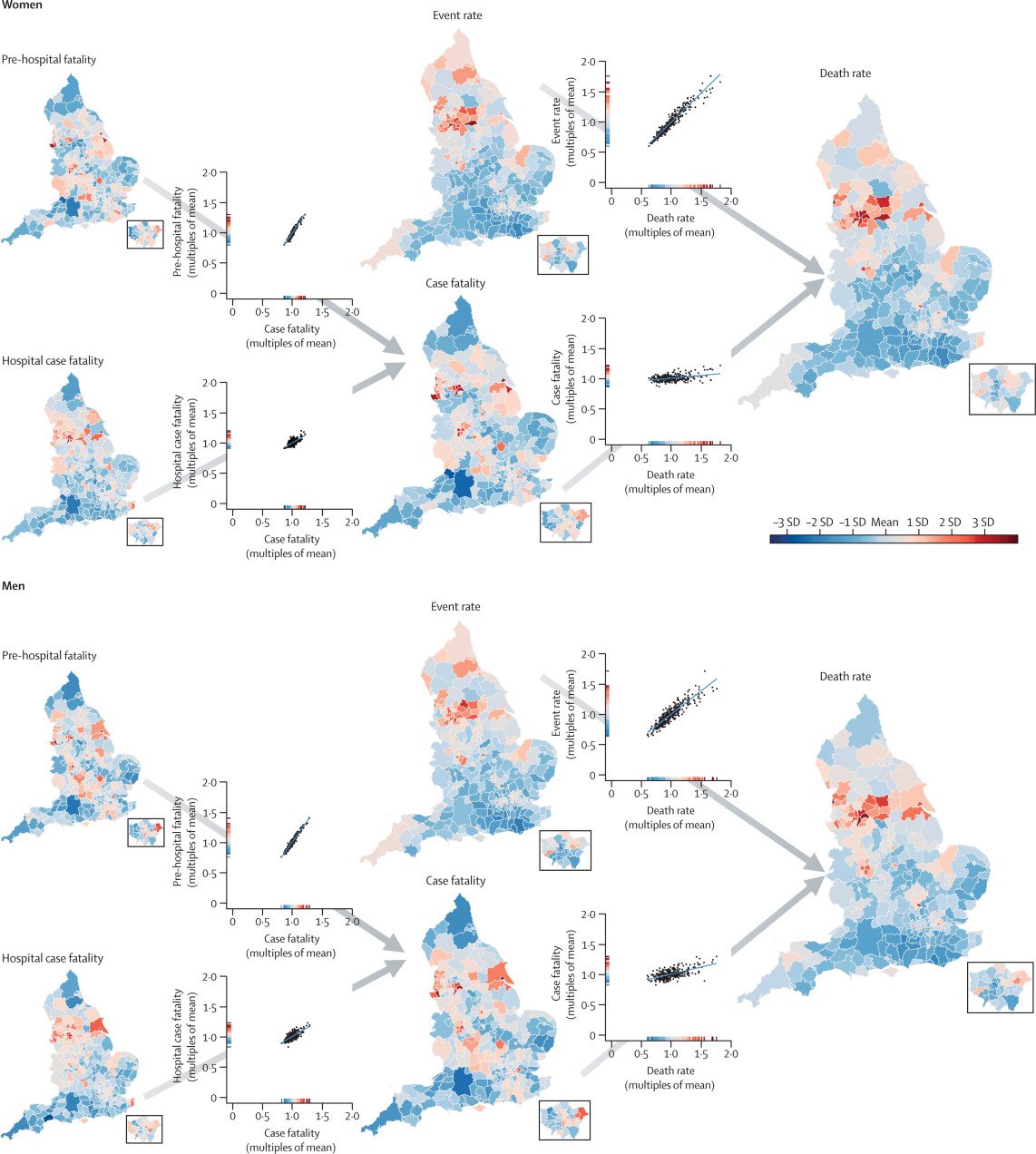

Figure 2Relationship between pre-hospital fatality and hospital case fatality

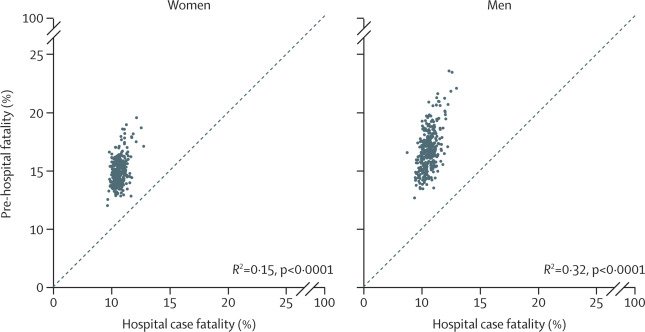

Figure 3Distribution of myocardial infarction mortality, event rates, pre-hospital fatality, and hospital case fatality by age group and sex, and male-to-female ratios

Each point represents one district. *Percentage of all myocardial infarction events. †Percentage of all myocardial infarction hospital admissions.

Table 2Proportion of variation in myocardial infarction mortality across districts explained by myocardial infarction event rates and case fatality, by sex and age group

Percentages show how much less variable myocardial infarction death rates would be if that contributor (event rate or case fatality) was at the same level in all districts in that age-sex group. Myocardial infarction event rates and case fatality act in a multiplicative manner in each district to produce the death rate and are not independent; thus, the contributions do not add to 100%.

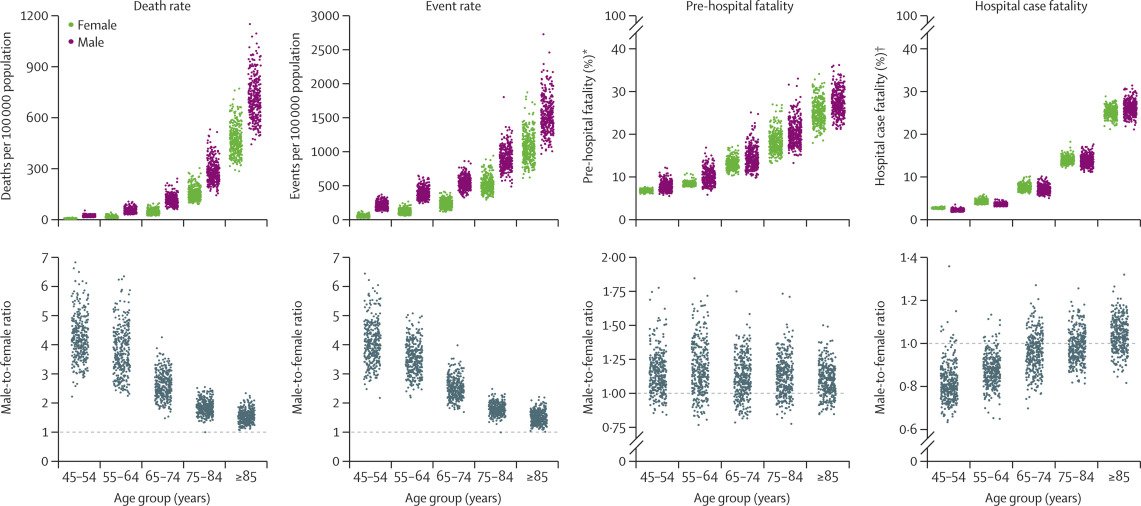

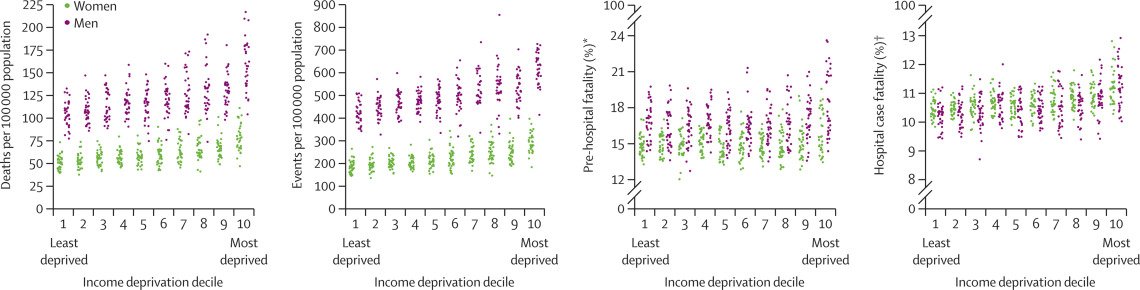

Figure 4Distribution of myocardial infarction mortality, event rates, pre-hospital fatality, and hospital case fatality by decile of income deprivation

Each point represents one district. *Percentage of all myocardial infarction events. †Percentage of all myocardial infarction hospital admissions.

Sensitivity analyses showed that inclusion of all acute myocardial infarction deaths within 28 days of any admission (regardless of whether the primary admission diagnosis was myocardial infarction or another condition; an additional 25 510 deaths) as post-hospitalisation deaths increased hospital case fatality by 4·7–8·2 percentage points and decreased pre-hospital fatality by 4·4–8·2 percentage points across different districts and the two sexes. As a result, the degree of variation in pre-hospital fatality among districts increased, but the overall ranking of districts in terms of high versus low hospital case fatality and pre-hospital fatality was maintained; the correlation coefficients between the results of the main and sensitivity analyses were 0·93 (women) and 0·95 (men) for district-level hospital case fatality, and 0·91 (women) and 0·94 (men) for district-level pre-hospital fatality.

Discussion

We found that variation in hospital case fatality made only a small contribution to the substantial geographical variation in myocardial infarction mortality in England from 2015 to 2018. A much bigger element of this variation in mortality arose from pre-hospital deaths and event rates. Hospital case fatality, nonetheless, varied across districts.

,

We did not include cases of myocardial infarction diagnosed as a secondary condition because the recording of secondary diagnoses is more variable than that of primary diagnoses, and the causes of secondary myocardial infarction, as well as the treatment pathways, might differ. Nationally, the inclusion of cases of myocardial infarction recorded as a secondary diagnosis would lead to around a 37% increase in total myocardial infarction admissions.

Cause-of-death assignment is based on more limited clinical information than hospital diagnostic codes—eg, in cases of pre-hospital cardiac arrest—and thus might be more subject to error.

It is unlikely, however, that cause-of-death assignment varies subnationally enough to affect the results.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

and only some included pre-hospital deaths.

,

,

,

,

,

Our estimated hospital case fatality of around 11% is consistent with the national audit data report in England,

and within the 4–17% range in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Because few studies used data on pre-hospital deaths,

,

,

,

,

,

there is little comparative data on total case fatality and especially on the percentage of events that lead to death before hospitalisation. Consistent with our finding across districts, these studies found that pre-hospital fatality was a larger contributor to case fatality than was hospital case fatality. Pre-hospital fatality also varied more across countries than did hospital case fatality.

,

,

Management of non-STEMI, which relies on risk stratification to decide on early versus delayed angiography and on optimal anti-coagulant and anti-platelet therapy, also accounts for some of the observed variations in hospital case fatality.

,

,

,

Finally, the use of secondary prevention therapies in the immediate post-myocardial infarction phase, which improves both 28-day and longer-term survival, also varies within England and across countries.

,

,

England and other high-income countries have implemented awareness campaigns for myocardial infarction symptoms,

but these programmes are rarely targeted and adapted to communities where pre-hospital deaths are high. Strategies to reduce mortality from cardiac arrest following myocardial infarction

,

include increasing CPR competence in the general public (Japan and Scotland),

,

with support by emergency services via telephone (New Zealand and Singapore);

,

using trained volunteer or fire, police, or health-service workers as first responders (Austria, Norway, and Ireland);

increasing the number of public-access defibrillators;

and alerting nearby CPR-trained responders using mobile phone alerts (Denmark and England).

,

The available data show that some of the potentially effective interventions, such as public-access defibrillators, are used less commonly than standardised facility-level interventions; the use of other interventions, such as bystander CPR, varies across and within countries.

,

,

These risks can be partly reduced through more ambitious and equitable preventive interventions, such as New Zealand’s recent zero-smoking policy and financial support for healthy foods.

Risk can also be effectively mitigated by individual-level primary and secondary prevention through counselling for smoking cessation, statin therapy, and treatment of hypertension and diabetes. In England, cardiovascular risk screening has been offered to approximately 33% of the eligible population, of whom only about 50% take it up, leaving many of those at risk unscreened and untreated; the extent of undertreatment varies across the country.

,

The decline in myocardial infarction mortality over the past five decades, driven by lower levels of smoking and other risk factors and advances in treatment both in primary care and specialist hospitals, has been a major clinical and public health success in high-income nations. Hospital case fatality is the element of the acute myocardial infarction pathway that is most relevant to those myocardial infarction patients who reach a facility, and most amenable to direct health-system intervention. However, with standardisation of hospital care following randomised trials, hospital case fatality now makes a smaller contribution to variations in myocardial infarction mortality within England and across high-income nations than do pre-hospital deaths and event rates. Nonetheless, the combination of our results and data on cross-country variations in hospital fatality show that further improvement in England is possible but requires a subnational focus where hospital case fatality remains high.

Our results also show that further scaling up population-based and individual-level primary and secondary prevention, as well as addressing the relatively large and highly variable pre-hospital fatality, are essential to reducing overall mortality. Strategies to achieve these reductions should be evaluated in randomised trials and in real-world conditions when new programmes are implemented. To ensure that these interventions translate to beneficial impact on death rates, there should be focus on parts of the country where each constituent of mortality is highest, and enhancement of registries to gather data on deaths outside the hospital setting, as currently done for hospitalised patients.

PA, PE, and ME conceived and designed the study. PA, HID, MD, and DF obtained and managed the data. PA, JEB, and ME developed the analytical strategy. PA conducted analysis in consultation with JEB and TR. PA, ME, JEB, and DPF interpreted the data and drafted the figures. PA and ME wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Other authors provided input to finalise the paper. PA, JEB, TR, and HID had full access to all data used in this study. PA and HID checked and verified the data used in the analysis. Due to data permission restrictions, not all authors were able to access the underlying data used in the study. All authors were responsible for submitting the article for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Moran (Resolve to Save Lives), Annika Rosengren (University of Gothenburg), Anoop Shah (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine), Darwin Labarthe (Northwestern University), Jean-Michel Gaspoz (Geneva University Medical School), Johan Sundstrom (Upsala University), Rod Jackson (University of Auckland), Tomasz Zdrojewski (Medical University of Gdansk), Yuan Lu (Yale University), and Ziad Obermeyer (University of California Berkley) for their suggestions for the Discussion section. We thank Vasilis Kontis (Imperial College London) for insights on the implementation of the statistical model. PA was supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinical PhD Fellowship (grant number 092853/Z/10/Z). TR was supported by an Imperial College President’s PhD scholarship. Funding was also provided by the British Heart Foundation (Centre of Research Excellence grant RE/18/4/34215), the Wellcome Trust (Pathways to Equitable Healthy Cities grant 209376/Z/17/Z), the Medical Research Council (MRC Centre for Environment and Health grant MR/S019669/1 and grant MR/V034057/1) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre. PE acknowledges support from the Dementia Research Institute at Imperial College. The study uses the UK Small Area Health Statistics Unit (SAHSU) data, obtained from NHS Digital and the ONS. SAHSU holds approval from the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group under regulation 5 of the health service (Control of Patient Information) regulations 2002 (section 251; reference 20/CAG/0028), and the National Research Ethics Service: London-South East Research Ethics Committee (reference 22/LO/0256). The work of SAHSU is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Public Health England (now UK Health Security Agency), and the NIHR through Health Protection Units at Imperial College London in Environmental Exposures and Health (NIHR-200880) and in Chemical and Radiation Threats and Hazards (NIHR-200922). This Article does not necessarily reflect the views of Public Health England or the Department of Health.